The Future of Cybersecurity: Human-Centred Design

Designing Security for the Human Experience - This article is part of a series.

I ended my previous research post saying that using behavioural science to influence people’s cybersecurity behaviours is not the answer. The situation is far more complex and nuanced than this (hence the long read).

Using behaviour change to influence how people interact with technology is addressing only the symptoms, and not the main cause when it comes to managing human risk. A more effective approach to cybersecurity is to shift the focus away from trying to change human behaviour and instead design technology to work securely for human interaction.

The proposed solution — “human-centred design”, involves taking into account people’s needs and limitations — the way we think, behave, and interact with technology when designing and building software and applications. By designing for humans, we can create technology that is both secure and user-friendly. Additionally, this approach prioritises usability, making security features intuitive and easy to use.

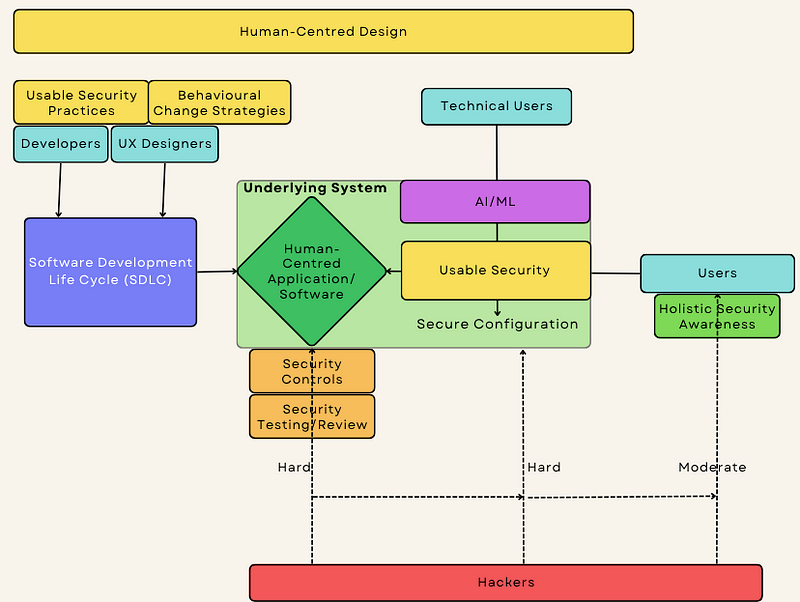

The proposed long-term solution is as follows:

- Apply Human-Centred Design to the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) — mostly by ensuring a “usable by design” approach (behavioural change intervention strategies can also be used here if needed).

- Use Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) to assist technical security professionals with the technological complexity of assessing and configuring app and system security.

- Move from the traditional ineffective security awareness approach to “holistic security awareness” strategies.

The Limitations and Consequences of Relying on Human Behaviour in Cybersecurity#

“Computers have enabled people to make more mistakes faster than almost any invention in history, with the possible exemption of tequila and handguns” Mitch Ratcliff, Digital Narrative Alliance

Cybersecurity has become an increasingly important concern in recent years, with growing numbers of cyber attacks and more severe impact than ever before. According to the 2022 Verizon Data Breach Incident Report, 82% of breaches involved the human element (e.g. social attacks, errors, misuse). Similarly, the UK government reported that in 2020, the majority of breaches suffered by UK companies were due to the compromise of employees’ user accounts.¹⁰

It’s no wonder that many companies are now spearheading the message that managing human risk is best achieved by influencing how people behave around technology. To back this up the industry is pushing the research with the goal of demonstrating how using behavioural science is the way forward to achieve better security outcomes. Searching through ScienceDirect papers matching words “security” and “behaviour” there are more than 300 articles published on this topic in the past 20 years. More than half of them came out in the last 5 years.

As I outline in the following sections, relying on changing human behaviour to reduce the risk of cyber attacks diverts efforts from focusing on the real problems and has significant limitations.

Security Awareness Is Not A Silver Bullet#

Ignoring the bigger picture of security is like trying to solve a puzzle with only a few pieces.

First up — reasons why many security awareness programmes are failing to elicit the expected behaviour changes in people. A recent 2023 paper entitled Rebooting IT Security Awareness — How Organisations Can Encourage and Sustain Secure Behaviours¹¹ reinforces what I wrote in the first part of my research — a lot of organisations are using security awareness products, but with little proven behaviour changes. In 2020 Americans were more aware of cyber threats but their online security hasn’t changed — quite the opposite. In 2022 this resulted in Cyber Security Awareness Month becoming a joke in the US.

Security Awareness In Isolation Is Ineffective#

One reason why Security Awareness strategies are ineffective is partly because they’re applied in isolation and don’t take into account many other factors. Security awareness strategies using behavioural science aim to persuade individuals to change.

Relying solely on security awareness programs for managing human risk is like locking the front door of a building but leaving the back door open.

The approach should be changed to become Holistic Security Awareness, which could use modern security awareness strategies but also making adjustments to the surrounding environment (culture, policies, systems) and aiming to reduce friction with security while ensuring employee productivity is protected in the process.

Culture is a particular important aspect which is often left out. The culture of an organisation sets the mood, defines how open it is in sharing successes and mistakes, and shapes the beliefs and attitudes that influence how people act.

Extra steps are needed to ensure behaviour change through the stages of the Security Behaviour Curve — concordance, self-efficacy, and embedding — for secure behaviour to become a routine. In the embedding stage for example, “the new secure behaviour has to be repeated many times to become embedded. With every repetition, we move forward on the path to it becoming automatic, but every time the old, insecure behaviour is carried out, we go 3 steps back. Companies need to take active steps to decommission old behaviours, and remove the cues or triggers for them — a technique called Intentional Forgetting that has been successfully applied in the introduction of new safety procedures. In IT security, the need to “take out the trash” — removing obsolete rules and terminology, changing user interface design and processes as well as policies — is currently not understood.“¹¹

Individual Differences#

A big limitation of security awareness strategies is the inability to be tailored to individual differences.

It has been shown that cybersecurity behaviours of employees within the same organisation differ despite receiving the same training and being subjected to the same policies. To tackle this, one of the classic rules of Security Awareness is to customise your program based on the audience. In most cases this is done based on department or role (field or remote teams, Executives, technical or non-technical teams) and/or geographical location.

However, prior research reports that there are many more individual factors that influence behaviour such as — an employee’s understanding, gender, computer skills and prior experience, attitude towards cybersecurity, age group, individual perception, personality type and traits.⁸ For example:

- An individual’s perception regarding cybersecurity threats is associated with employee risky behaviour.

- Rate of younger age groups engaging in risky cybersecurity behaviour is higher than in older ones.

- Personality traits and personality types are correlated with cybersecurity behaviours — for example conscientiousness is associated with the propensity to follow rules and norms that are set by society.

Culture also plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s attitude towards security measures. When designing security awareness messages, it is essential to consider cultural factors as people tend to respond better to messages that align with their cultural values and beliefs.³ With most workplaces being multi-cultural these days, tailoring security awareness programs to suit everyone is a major challenge, if not impossible.

Taking into account all of these individual factors can be extremely difficult to achieve. The temptation for innovative companies is to achieve this via individual profiling. This would, in theory, be achieved by using massive data collection points and analysing them through Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning techniques, allowing the creation of tailored nudges⁹ and security awareness strategies. With this approach we are quickly entering ethical grey areas, concerning privacy, surveillance capitalism and data collection. Companies can end up taking the Facebook approach and use the collected data to assess how risky a person is. Gathering personal data can also enable these companies to see what people’s online habits are, or if certain personality types are deemed more risky. This would end up looking like is a dystopian future and hopefully we don’t go down this path, through proper policy and law regulations.

Behavioural Science Limitations#

Governments and companies are investing heavily in shaping online behavior, and their efforts would be most effective if they relied on robust evidence of actual human behavior.

In their Manifesto for Applying Behavioural Science, the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) talk about the criticism in the field and its (many) limitations. One of the most important limitations of behavioural science (BS) is the “replication crisis” — the reliability of BS findings, namely how well the BS case studies and their respective results can be replicated? Human behaviour and psychology are extremely complex. When studied, they have a plethora of variables which don’t yield the same results when taken in isolation from each other. Therefore it’s extremely challenging to apply conventional evidence-based methods to BS case studies and small changes in study variables yields wildly different results. This makes BS findings unreliable.

In addition, as I mentioned before, using behavioural change strategies to influence people’s cybersecurity behaviours sounds good in theory, but can be very difficult to implement. This is due to constraints such as company size, culture, budget and resources, business values and goals, and various technical aspects (specific application features, configuration and customisation options, the organisation’s technical capability to configure and customise apps).

The aim should be to initiate a process to gain a deeper comprehension of the difficulties involved in altering cybersecurity behavior. People need to be able to comprehend and implement the advice, and they must also be motivated and willing to do so, which necessitates changes in attitudes and intentions.³

Evolution#

Human evolution is probably one of the biggest reasons why using behavioural science to influence our cyber habits can be less effective than we expect.

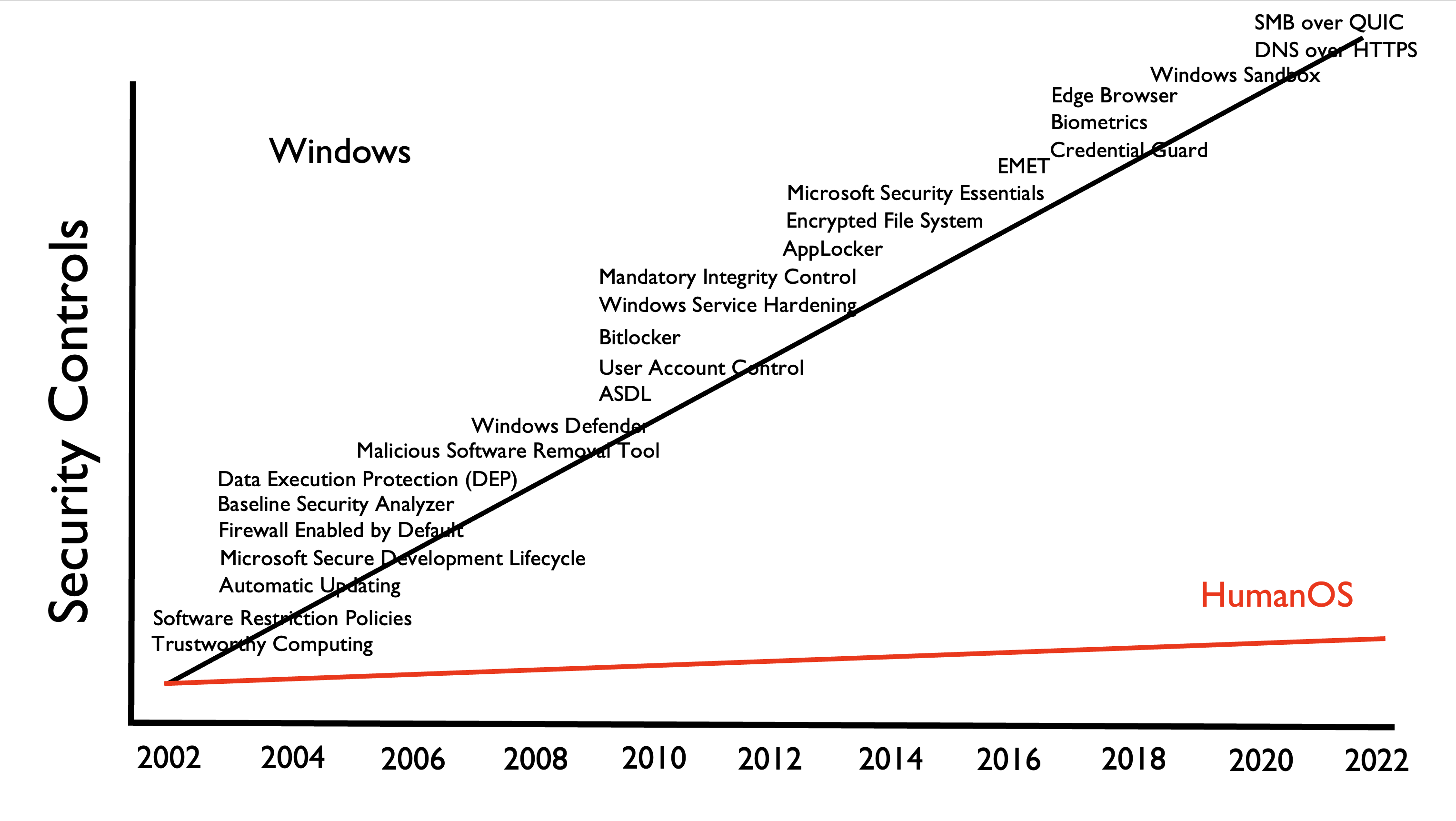

The human Operating System, which has evolved from millions of years ago to what it is today, is just one of those legacy systems that you just can’t patch or ever get rid of. While commendable, efforts to change people’s behaviour around digital security is not an effective long term solution. Looking at fixing the digital environment around us instead could prove to be a much better option.

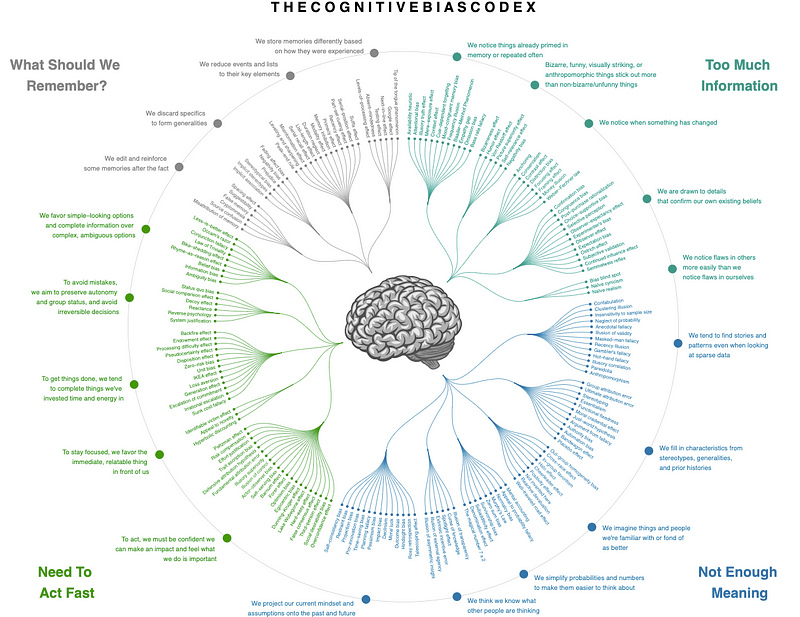

By trying to influence security behaviours we are basically blowing against the wind. Our brains have stayed the same for hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of years, and as natural consequence of human evolution we developed cognitive biases.

Cognitive biases cannot always be avoided and living life in a state of continuous vigilance and security awareness is not practical at all. Being constantly aware of security measures can be stressful and lead to a phenomenon known as “security fatigue”, which can negatively impact the well-being of both organisations and society as a whole.³

Paradoxically, being in high levels of vigilance is also working against the intended goal, as the famous invisible gorilla experiment cognitive psychology study shows. The study was designed to demonstrate the phenomenon of “inattentional blindness,” which refers to the inability of people to detect unexpected and important events while they are focusing their attention on something else. The results of the study have important implications for areas such as traffic safety, eyewitness testimony, and human-computer interaction. This can lead to a number of potential problems in the context of human-computer interaction, including:

- Overloading of attention: When people use computers, they are often presented with a lot of information and stimuli, which can cause them to become overwhelmed and miss important information.

- Inattentional blindness: Just as in the gorilla experiment, people can miss important information or events on a computer screen if they are focused on a specific task and not paying close attention to the surrounding environment.

- Error prone behavior: When people are distracted or miss important information, they are more likely to make mistakes or engage in error-prone behavior while using a computer.

Over the years, renowned scholars such as Daniel Kahneman, Charles Duhigg, and Thaler & Sunstein have contended that people make swift decisions based on cues developed by the brain through heuristics and biases. In their canonical work “Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness”, Thaler & Sunstein suggest that the decision-making process of humans is not rational and is aided by illogical tendencies, which are frequently mental shortcuts or internal references that enable individuals to arrive at decisions or judgments quickly, referred to as heuristics. Duhigg and Kahnemann also argue that individuals make choices and decisions quickly and often automatically.⁸

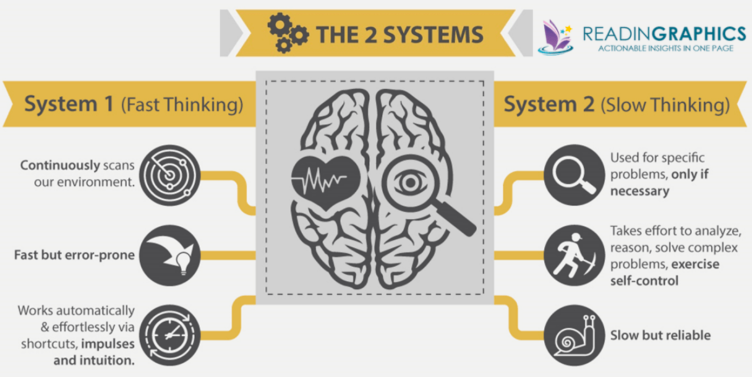

Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast and Slow” book revolutionised how we see our brain. It explores the dual-system model of the human mind. System 1 is intuitive, emotional, and automatic, while System 2 is deliberate, logical, and reflective. The book argues that System 1 is prone to biases and errors, while System 2 is limited in its ability to correct them, leading to systematic thinking errors. It is revealed that emotions play a critical role in shaping our thinking and decision-making, and that we are not always aware of the impact they have.

According to Kahneman’s research, System 1 thinking, which is intuitive and automatic, dominates our day-to-day thinking and accounts for the majority of our decision-making.

In a Click-bait or Phishing email scenario, System 1 thinking would likely be activated because the email subject/click-bait title is designed to be attention-grabbing and appealing to our emotional and intuitive responses. System 2 might also be activated if we become skeptical or curious about the content of the title and decide to read further to make a deliberate judgment.

Research has shown that strong emotions, such as fear, anger, or excitement, can impair or limit the activation of System 2 thinking, as our emotions can interfere with our ability to make deliberate and reflective decisions.

Additionally, fatigue, lack of motivation, and high cognitive load can also limit the activation of System 2 thinking, as these factors can reduce our ability to engage in deliberate and reflective thinking. Moreover, the influence of System 2 thinking can also be limited by social and cultural factors. For example, research has shown that people are more likely to rely on their intuitive, automatic thinking when they are in a group, as social pressure can reduce their willingness to question the dominant opinions and beliefs of the group.

Throughout our daily life everything is fighting for our attention. From the time we wake up to the time we go to sleep, our thoughts wonder everywhere. Life’s minutiae is causing constant switching between System 1 to System 2 thinking — Tweets, kettles boiling, traffic jams, due deadlines and much more. To make matters worse, this is exacerbated by adding more and more technology into the mix — some of it deliberately designed to trigger our System 1 (as we’ll see in the next section). All this makes us humans fallible and cause us to inevitably make mistakes, such as using weak passwords or clicking on suspicious links. All it takes is a little inattention. That’s why even the most well-informed and security-conscious individuals can fall victim to social engineering attacks.

A paradigm shift is needed, from “influencing human behaviour to make less mistakes” to “accept that humans will make mistakes”. It’s similar to the adage of assuming breach, or not “if” but “when”. Once this happens the re-thinking of applications and systems can start. Compared to our minds, the digital technology we created in the past 50 years is still in its infancy — it would be a much more effective and easier solution to change how it is designed and built. This is not something that is going to happen overnight. However, this is not an excuse to not shift the mindset in that direction.

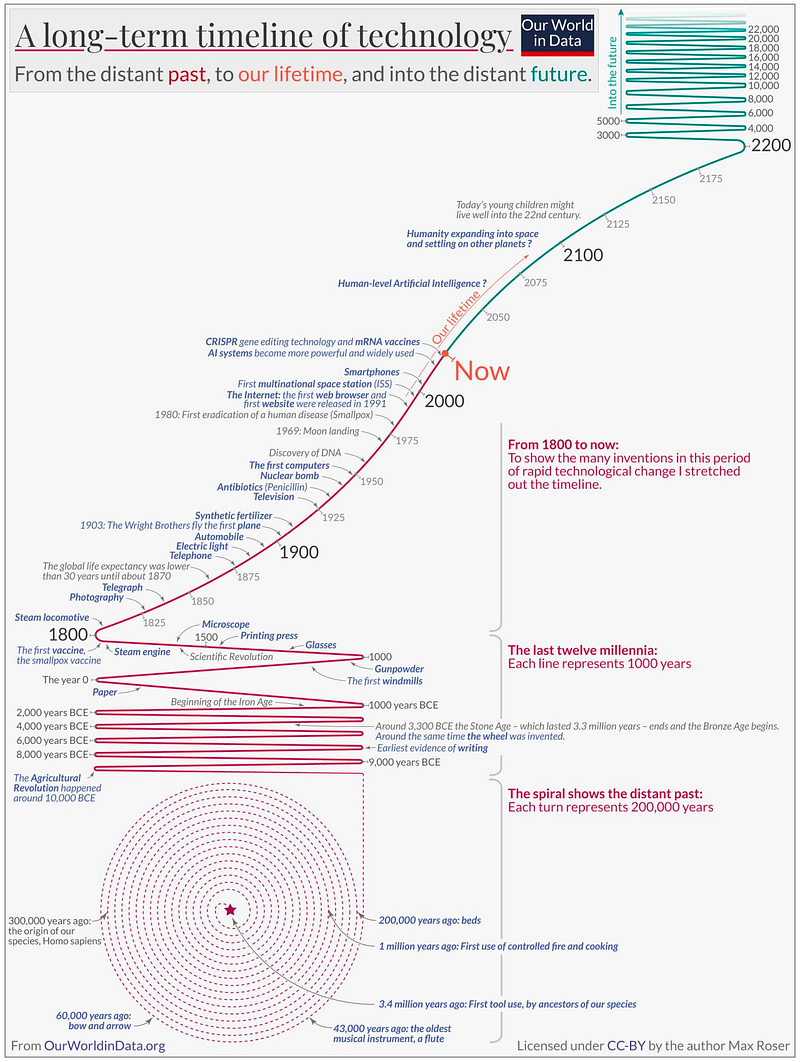

On the above graph, digital technology occupies a smaller space in time than a dot on the timeline spiral.

How Behavioural Science and UX Undermine Cybersecurity#

Behavioural Science and User Experience design are implemented successfully in building popular software applications which will be used with their intended purpose — but for all the wrong reasons.

Digital tech is mostly created with the mindset that it will be used rationally (i.e. using our System 2, as referenced in the previous section). This way it won’t have unintended consequences, such as insecure misconfigurations and privacy breaches. However, current use of behavioural science and User Experience (UX) design in some of the most popular apps we use is working against this concept, and undermines cybersecurity in the process. Continuing on the idea from the previous section, software like social media apps and many others are designed to grab our attention by engaging our System 1 thinking. In UX, these are called dark patterns.

A simple Google Scholar search shows how much evidence there is that social media platforms manipulate our behavior to keep us addicted to constant scrolling through ads and content. This was seen in instances such as the online extremism that contributed to the 2021 Capitol attack and vaccine misinformation that exacerbated the coronavirus pandemic. And unfortunately it’s not the only digital technology which has this business model — the very lucrative gaming industry has done much of the same. Ads and online media outlets work in a similar fashion.

Anything can be used with both good and bad intention. The same attention-grabbing designs and efforts could be used with good purpose in mind, such as building more usable security apps (e.g. password managers) or helping people adopt more secure cyber habits. There are good examples of how UX design can be used for improving user interaction with technology. Unfortunately, there is no incentive for big tech companies to do this, it just costs them more money and it doesn’t really add value to their business. This is ironic, because a shift in their attitude towards how they design their apps would benefit them and everyone else in the long-term — it could minimise costly security breaches and incidents. And they could also be a trend setter and an example for positive change against UX dark patterns. This can provide a boon to their brand image, which would hopefully persuade other tech companies to follow.

Otherwise, the other route is through private organisations making an effort to change things through awareness — such as the Center for Humane Technology. If companies don’t like the carrot, perhaps the stick can persuade them instead, through strict laws and regulations.

Technological Complexity#

According to a recent report by Gartner, it is predicted that by 2025, more than 50% of major cybersecurity incidents will be caused by a shortage of skilled professionals or human error, partly due to the increasing prevalence of social engineering attacks and insufficient attention to data hygiene.¹¹

There’s a reason why there’s a 3 million cyber security professional skill gap worldwide. The complexity of modern technology makes it difficult for the average person to understand and navigate securely, let alone configure it without making mistakes and causing incidents. It’s not only the complexity, but there is also more and more digital technology around us, being developed at breakneck speeds as an effect of the Covid-19 pandemic. People can’t keep up with this trend, humans aren’t robots, we haven’t evolved for long enough to cope with the technological complexity we created. This is the reason why human errors and misconfigurations are some of the most common causes of cybersecurity incidents. Entrusting people with the secure configuration and interaction of digital technology is not working. Throwing more cybersecurity professionals at the problem is not working either, at this rate we can’t catch-up. What can be done to get out of this nightmare?

Could Artificial Intelligence Help Fill The Skills Gap?#

A normal computer has hundreds or thousands of pieces of software installed on it. Their code, configuration, and interaction is what creates the security risk. This is why hackers can move laterally from one vulnerable or misconfigured software to the other, until they reach the crown jewels. As cybersecurity professionals with limited skillsets — Security Consultants, Penetration Testers, Forensics Analysts, Security Engineers, etc, we are narrowly focusing on only a handful of technologies. We have limited knowledge to assess their interaction, security gaps and configure them. At best, a system deemed secure lasts for a narrow window of time and tends to change to being insecure quite rapidly.

Perhaps the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) can rescue us from the technological flood we created.

Also, in recent decades, there has been a significant rise in cyber threats that are becoming increasingly sophisticated and difficult to detect using conventional protection tools. AI, ML, and deep learning are among the top techniques that could enhance the detection capabilities and engines for computer network defence against such threats. The use of AI and ML can expedite the identification of new attacks and serve as a potent means of generating statistical insights that can be transmitted to endpoint security systems. Given the large volume of attacks and a scarcity of cybersecurity professionals, AI and ML are becoming indispensable tools. AI and ML have demonstrated their worth by deciphering data from various sources and spotting crucial relationships that people would miss.¹¹

Taking into consideration current AI and technology capabilities, and processing power, AI programs could have awareness and access of every piece of software and hardware on a computing system. They would have the capability to understand how they interact together and predict if their interaction and configuration would pose big cybersecurity risks to the system.

Being capable of many calculations of possibilities, such an AI can explore all the security misconfigurations and software interactions (e.g. open ports and permissions, code flaws, etc) that would end up in security incidents, suggesting the most secure configuration customised for the system it’s assessing. This would close the cyber kill chain for a possible attack and minimise the risk exposure. An example of a lighter version of this is Microsoft’s Secure Score — which I imagine will get a boost soon using OpenAI’s capabilities.

Realistically, such a program would likely require significant resources. The number of software and hardware present on the target system being assessed could have an impact on the capabilities required for such an AI program. Data, complexity, and expertise are likely to be the most resource-intensive factors, and maintenance will be an ongoing effort. However, such an AI program would provide immense benefits such as:

- Enhanced Threat Detection — identify patterns and anomalies in network traffic and system logs, allowing for faster and more accurate threat detection.

- Real-Time Incident Response — analyse and interpret security alerts, helping security teams to respond to incidents in real-time.

- Improved Malware Detection — detect malware through the analysis of file characteristics, behaviour, network activity.

- Advanced Phishing Detection — identify suspicious emails and phishing attempts by analysing message content, sender information, and other relevant data.

- Accurate Risk Assessment — evaluate the potential impact and severity of security incidents, enabling security teams to prioritise their response and allocate resources effectively.

- Proactive Threat Hunting — analysing historical data and identifying patterns of attack, assisting security teams in identifying potential vulnerabilities and proactively hunting for threats.

- Improved Access Control — assist in enforcing access control policies by analysing user behaviour and detecting anomalies or suspicious activity.

- Smarter Incident Investigations — assist in incident investigations by analysing data from multiple sources and providing context and insights that would otherwise be difficult to uncover.

- Automating Routine Security Tasks — automate routine security tasks such as patch management, vulnerability scanning, and user access management, freeing up security teams to focus on more complex issues.

- More Effective Threat Intelligence — analysing vast amounts of data from multiple sources, helping security teams to better understand the evolving threat landscape and develop more effective threat intelligence strategies.

Some of the above capabilities are already implemented by some security vendors offering EDR or XDR technologies, albeit immaturely and not holistically integrated with all operating systems or other vendors.

There is of course the question of AI’s security. There are already efforts to tackle this problem, at least from NIST’s side. Hopefully more will follow their example.

Usable Security Not Integrated in Software Development#

System security departments typically view users as a potential threat that must be managed. It is widely accepted that many users are negligent and unenthusiastic about system security. Research discovered that users can unintentionally or deliberately compromise computer security measures like password authentication. However, upon closer examination, it was found that such conduct is often due to inadequate security implementations. Therefore, the research suggests that security departments adopt a user-centric design approach to improve the situation.¹

A lot of breaches occur not because of human errors, but due to poor software design which doesn’t take into account user context and human factors. Integrating usable security in software development practices is the key.

Traditionally, security solutions were designed primarily with highly skilled technical users in mind. However, this approach exposed flaws and inadequacies in existing methods of securing systems, highlighting novel threats and difficulties such as:⁷

- Proposed security solutions were unusable

- Perceptions of the efficacy of security practices impacted the adoption of security technologies

- Protection mechanisms were frequently under-utilised or disregarded entirely

- Security has been erroneously treated as an add-on feature rather than a fundamental aspect of the system that necessitates meticulous planning and design

- Security-focused systems frequently overlooked the human element during design and implementation, leading to the perception that people are the “weakest link” in the security chain

Usable security refers to the idea that security mechanisms and features should be designed with the average user in mind, to make them easy and convenient to use, while still providing a high level of security. It is an approach that recognises that security is only effective if users are able and willing to use it correctly, and that this requires taking into account the user’s cognitive limitations, motivations, and context of use.

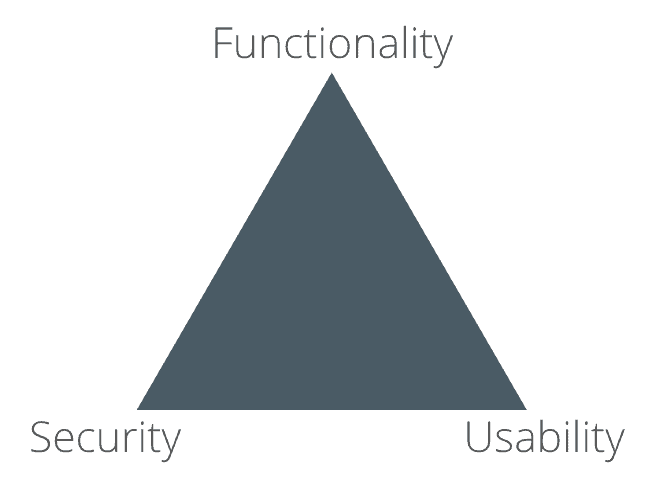

Usable security seeks to balance the competing demands of security, functionality, and usability, by designing security features that are effective, efficient, and satisfying to use. This can include things like clear and informative warnings and feedback, intuitive and streamlined user interfaces, and well-designed policies, applications and systems that strike the right balance between security and usability.

Cyber defenders could also greatly benefit from usable security being integrated in the tools they employ during day-to-day operations. SOC security managers and analysts concur that cutting-edge technologies would be inadequately utilised if they are challenging to learn or suffer from poor usability. Consequently, their attention tends to shift towards the tools rather than the incidents.⁷

The Infamous Usability-Security Trade-off Myth#

In the past, the conventional wisdom was that security and usability were opposing forces: a highly secure system was believed to be less practical and more frustrating, while a more versatile and powerful system was thought to be less secure. This either/or thinking often led to the development of systems that were neither user-friendly nor secure.⁴

Usable security is about designing security features and mechanisms that are easy to use, without sacrificing security or functionality. The usability-security trade-off myth is a misconception and this is the first thing that needs to change in the cybersecurity and software development fields. Security fatigue arises when the triangle leans too heavily towards security and the demands become overwhelming for the users. Hence, it is important to strike a balance between system security and usability.

The “Security, Functionality and Usability Triangle” is a model that highlights the challenge of balancing three goals that often clash with each other — security, functionality, and ease of use. According to this model, when one of these aspects is prioritised, the other two are weakened. However, this model has been shown to be a misconception, and implementing it can lead to systems that are neither secure nor usable.

(Un)Usable By Design#

“We’re headed into a dangerous time, when our society is run on digital platforms, and UX isn’t leading the way to ensure that those tools are usable” — CreativeGood

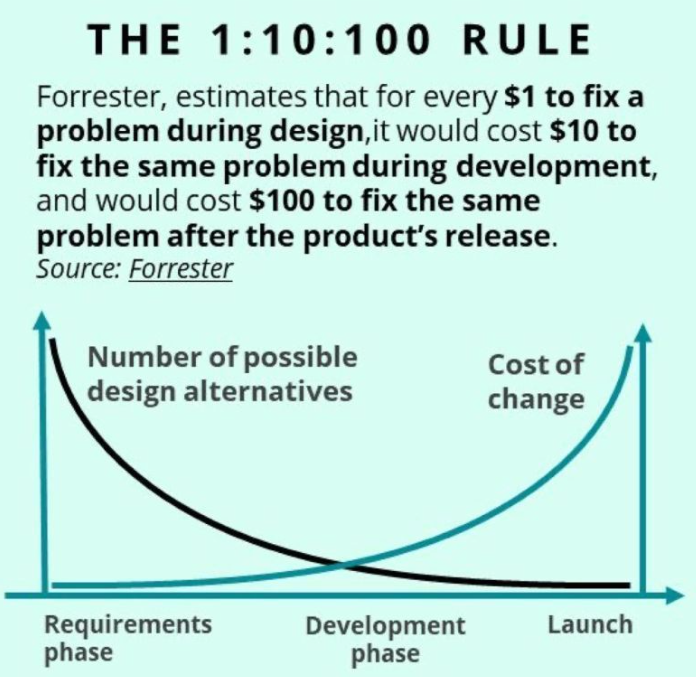

It’s a well known fact that integrating features in the design phase of a project is a lot less expensive than integrating the same features at the end of after the project is completed. This is the idea behind the “secure by design” — a core cybersecurity principle.

Similar to building a house, it’s easier to plan and lay a solid foundation from the start than having to fix cracks and leaks later.

Currently security awareness — i.e. educating the users how to use software in a secure manner, is trying to address security issues at the end of the process, when “unusable” production software applications reach mass usage. At that point it is much more difficult and expensive to add “usability” into existing applications.

Similar to the “secure by design” principle, it would be much more cost effective and efficient to design and create software and applications with the user in mind from the beginning, rather than addressing the leftover gaps at the end. The shift needs to be towards a “usable by design” mindset. Secure software development training and cybersecurity courses need to make this clear for future experts in these fields. Like planting a garden, it’s easier to prepare the soil and plant the seeds correctly from the beginning than trying to fix it after the plants have grown.

Systemic Issues in Secure Software Development#

Despite what’s mentioned above, very little attention has been paid to whether and how security features are made usable.

Most software development companies, especially startups, are incentivised by things like improving software deployment speed or growing their user base. Unfortunately there is very little incentive for making more secure software, especially early on in a company’s existence — this generates a dangerous mentality trend.

In November 2022 long-standing usable security advocate and researcher Angela M. Sasse has published a paper about the underlying reasons why usable security doesn’t make it into the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC). The paper is entitled How Does Usable Security (Not) End Up in Software Products?⁶ and I summarised the main findings in a recent article.

The research proposal emphasises that software must be both secure and usable for users to appropriately use security features.

There are many factors at the root of why usable security doesn’t make it into the SDLC. The most pressing ones are:

- Lack of awareness about the connection between security and usability

- Misconception — especially around the trade-off myth that usability and security have to be weighed against each other

- Missing knowledge

- Communication and cultural issues

- Limited resources — budgets, time, and the prioritisation of features and functionality to the detriment of usable security

To improve the adoption of usable security, there needs to be better awareness and interdisciplinary collaboration between academia and industry, along with measures that support a holistic usable security process — such as changes to the software development process (SDP) and resources.

The recommendations on how to achieve this are as follows:

- Build up awareness for usable security within the software development practices and impart knowledge to those involved (i.e. the software developers, UX developers, and stakeholders).

- A potentially effective way to achieve this is through behavioural change intervention strategies.

- Understand user context by improving communication between security and usability experts.

- Integrating Usable Security with SDCL

- Measure and track usable security — instead of the old “trial and error” approach use A/B testing, beta tests, active feedback gathering, or reduced number of support tickets opened by users.

- Utilise usable security champions — professionals with interdisciplinary knowledge in usability and security as well as taking care of usable security.

- Usable Security Defaults and Tooling — The general approach of “security by default” principle should be turned into"usable security by default” instead.

The Solution: Human-Centred Design in Cybersecurity#

It’s always easier to go with the wave, not against it. That is, accepting our human condition. Attempting to fix the user as a means of achieving security is a futile endeavour. Pursuing such goals merely distracts us from addressing the actual issues. Usable security is not synonymous with compelling people to comply with our wishes.⁴ Instead of relying on changing ourselves, why not aim to change the technology which we create in the first place?

Everyone likes analogies, so think of the Internet as a road and digital technology as a car. The assumption is that cyber attacks, similar to car accidents, are caused by human errors. Instead of aiming to have professional drivers behind each seat, we can make the cars and roads safer instead, and easier to drive. Sure, it’s still good to have the seatbelt on and hands on the wheel, at least until driverless cars are completely safe.

I’ve ended my last article mentioning that using behaviour change to influence how people interact with technology is addressing only the symptoms, and not the main cause when it comes to managing human risk. A more effective approach to cybersecurity is to shift the focus away from trying to change human behaviour and instead design technology to work securely for human interaction.

The need to construct secure systems that users can comprehend and properly utilise in their specific usage scenarios is not a novel idea. It dates back to 1883 when Kerckhoff enunciated 6 design principles for military ciphers, the 6th one stating “the system should be easy, neither requiring knowledge of a long list of rules nor involving mental strain”. Almost 100 years later, Saltzer and Schroeder’s groundbreaking research on safeguarding data in computer systems introduced eight principles that can direct the development of protection mechanisms and assist in their implementation, minimising the likelihood of security vulnerabilities. One of them is the concept of psychological acceptability, which they described as follows: “It is essential that the human interface be designed for ease of use, so that users routinely and automatically apply the protection mechanisms correctly. Also, to the extent that the user’s mental image of his protection goals matches the mechanisms he must use, mistakes will be minimised. If he must translate his image of his protection needs into a radically different specification language, he will make errors” Finally, the usable security community has long sought to shift this viewpoint. As an example, two decades ago, Sasse and her team, in keeping with ISO 9241–11:1998, identified four critical elements that must be harmonised to ensure that the security function is user-friendly and compatible with human behaviour.⁷

A system that is overly complex can result in users making errors and bypassing security measures altogether. If software and applications are not designed with the human user in mind, they can be difficult to use and may not provide adequate protection. In addition, confusing or complicated security features can cause users to simply bypass them, leaving their information vulnerable to attack.

This “human-centred design” approach involves taking into account people’s needs and limitations — the way we think, behave, and interact with technology when designing and building software and applications. By designing for security, we can create technology that is both secure and user-friendly. Additionally, this approach prioritises usability, making security features intuitive and easy to use. It can reduce the reliance on the end-user to navigate and use the technology securely and thus reduce the risk of human error.

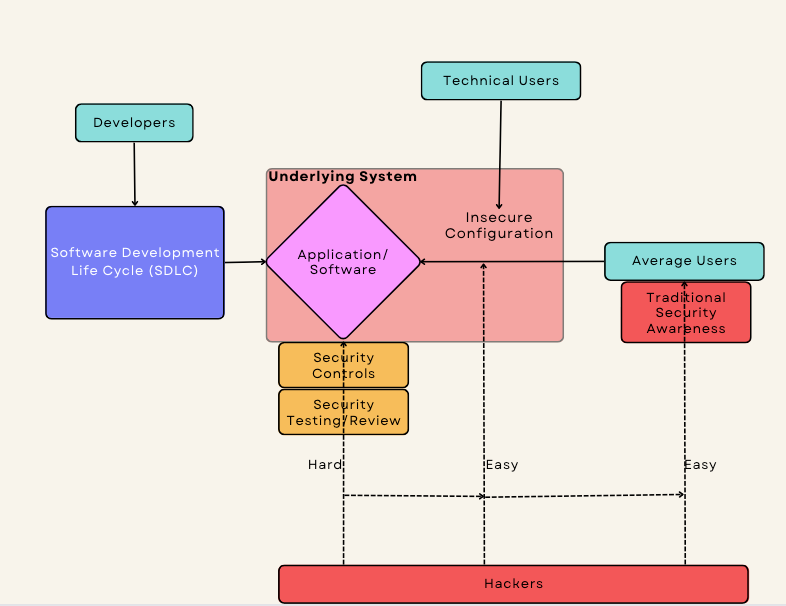

This is a very simplified picture of where the situation sits today:

- There are decent technical security controls in place to protect or test applications and software

- This forces hackers to go for the easiest targets — exploiting the users or the misconfigured systems and apps (in terms of their security settings)

- Reasons

- Users are vulnerable due to Security Awareness failing to influence their behaviour

- Applications and software are difficult to configure securely due to their underlying complexity and interaction with other apps and software

The proposed long-term solution is as follows:

- Apply Human-Centred Design to the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) — mostly by ensuring a “usable by design” approach (behavioural change intervention strategies can also be used here if needed).

- Use Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) to assist technical security professionals with the technological complexity of assessing and configuring app and system security.

- Move from the traditional ineffective security awareness approach to “holistic security awareness” strategies.

Developers and UX Designers could work together to integrate usable security into the software design requirements, and create applications which take into account human needs and limitations.

AI/ML can be used to assess an application’s security settings and interaction with other software on the system to come up with an effective security configuration which minimises attack risks. This will go alongside traditional security controls and testing (i.e. penetration testing, application testing, etc) for defence-in-depth.

And finally, having a holistic security awareness would mean making adjustments to the surrounding environment (culture, policies, systems) and aiming to reduce friction with security while ensuring employee productivity is protected in the process.

Putting Human-Centred Design Into Practice#

Security departments typically view users as a potential threat that must be managed. It is widely accepted that many users are negligent and unenthusiastic about system security. Research dating as far back as 1999 discovered that users unintentionally or deliberately compromising computer security measures like password authentication is often due to inadequate security implementations. The suggestion back then was to adopt a user-centric design approach to improve the situation.¹ As global investment company Vista Equity Partners acquires KnowBe4 (awareness training and simulated phishing platform leader), the message is still that the main focus should be put on making humans more secure instead of making security more usable from the start.

While the concept of human-centred design in cybersecurity may seem simple in theory, putting it into practice can be challenging. It requires a change in mindset, moving away from the traditional security-first approach and towards a user-first approach. It also requires collaboration between multiple teams, including security experts, designers, and developers.

Implementing human-centred design in cybersecurity involves users in the design and development process. This can help to ensure that the technology being developed is user-friendly and that the security measures are tailored to the way users think and behave. Additionally, conducting user research, usability testing, and user feedback can help to identify potential security issues before they become a problem.

Implementing human-centred design in cyber security requires a collaboration between designers, developers, and security experts. Designers must understand the threats and risks involved in cyber security, while security experts must understand the importance of usability and user experience. Together, they can create software and applications that are both secure and user-friendly.

Another important aspect of human-centred design in cybersecurity is to take a holistic approach and consider the entire user journey. This means thinking about how users will interact with the technology, not just at the time of login or when entering sensitive information, but throughout the entire process. By considering all the touch points, it’s possible to identify potential vulnerabilities and design solutions that are tailored to the user.

Finally, it’s important to continuously evaluate and improve the design. Security threats are constantly evolving, and the technology used to combat them must evolve as well. This means regularly reviewing and updating the design to ensure it remains effective in protecting against new threats.

Leading The Change#

And who will be leading this change you ask? Probably not the security vendors, as there is little incentive for them to do so.

Instead, there are many big names in the cybersecurity field who set the tone in the industry.

These organisations ensure that future generations of security professionals are equipped with the right skills and mindset to address current and future needs. The same cyber security professionals will be the ones to lead the change in mindset, educate their customers, and work with vendors to implement the human-centred design approach.

Measuring the Success of Human-centred Design in Cybersecurity#

Once human-centred design has been implemented, it’s important to measure its effectiveness in order to understand its impact and identify areas for improvement. The success of human-centred design in cybersecurity can be measured in a number of ways, including:

- User satisfaction: One of the key indicators of the success of human-centred design is user satisfaction. This can be measured through surveys, interviews, or other methods to gauge how well the technology is meeting the needs of its users.

- Security incidents: Another way to measure the success of human-centred design is by monitoring the number of security incidents. If the number of incidents decreases as a result of the new design, it suggests that the design is effective in reducing vulnerabilities and protecting against threats.

- Compliance: Compliance with industry standards and regulations is also an important measure of success. Human-centred design should aim to comply with relevant standards and regulations to ensure that the technology is secure and meets the necessary requirements.

- Return on investment (ROI): Finally, it’s important to measure the return on investment (ROI) of human-centred design in cybersecurity. This can be done by comparing the costs of implementing human-centred design with the benefits in terms of reduced security incidents, increased user satisfaction, and improved compliance.

Measuring the success of human-centred design in cybersecurity is essential for understanding its impact and identifying areas for improvement. By monitoring user satisfaction, security incidents, compliance, and ROI, it’s possible to evaluate the effectiveness of the design and make necessary adjustments.

The Future of Cybersecurity is Human-Centred Design#

The proposed long-term solution won’t be an over-night endeavour. It is probably at least a 10-year journey to shift the thinking from what it is today to human-centred design. It is also not going to guarantee that people won’t continue to create security incidents. However, all of this is not an excuse to start heading into the right direction.

It’s time to move away from the traditional human behaviour change approach in cybersecurity and embrace human-centred design. By embracing human-centred design, we can create a more secure digital world that is better suited to the way people think and behave. This approach can help to mitigate the risks associated with human error and lead to more effective and sustainable cybersecurity strategies.

Cybersecurity is a critical issue that affects everyone in today’s digital world. The current approach of trying to influence human behaviour to behave more securely is no longer enough. Instead, the future of cybersecurity lies in human-centred design that ensures software and applications are designed and built to work securely for human interaction.

The implementation of human-centred design in cybersecurity may not be a simple task, but it is essential for creating a more secure digital world. It requires a change in mindset, moving away from the traditional security-first approach and towards a user-first approach. It also requires collaboration, user involvement, and continuous evaluation, but ultimately it leads to a more effective and sustainable approach to cybersecurity. Additionally, by taking a holistic approach and continuously evaluating and improving the design, it’s possible to create a more effective and sustainable approach to cybersecurity.

The future of cybersecurity is about designing for people and not just for the technology. It’s about designing for the way people think, behave, and interact with the technology. It’s about creating a more secure digital world for everyone.

Research References#

- [1] Users are not the enemy — Angela Sasse (1999)

- [2] Emotion and cognition and the amygdala: From “what is it?” to “what’s to be done?” — Luiz Pessoa (2010)

- [3] Cyber Security Awareness Campaigns: Why do they fail to change behaviour? — Angela Sasse (2015)

- [4] Stop trying to fix the user — Bruce Schneier (2016)

- [5] CSET — A National Security Research Agenda for Cybersecurity and Artificial Intelligence (2020)

- [6] How Does Usable Security (Not) End Up in Software Products? Results From a Qualitative Interview Study — Angela Sasse (2022)

- [7] User Experience Design For Cybersecurity & Privacy: Addressing User Misperceptions Of System Security And Privacy — Borče Stojkovski (2022)

- [8] Nudges and cybersecurity: Harnessing choice architecture for safer work-from-home cybersecurity behaviour — Monasadat Fallahdoust (2022)

- [9] Your Behaviours Reveal What You Need: A Practical Scheme Based on User Behaviours for Personalised Security Nudges (2022)

- [10] Is cybersecurity research missing a trick? Integrating insights from the psychology of habit into research and practice (2023)

- [11] Artificial Intelligence Applications in Cybersecurity (2023)

- [12] Rebooting IT Security Awareness — How Organisations Can Encourage and Sustain Secure Behaviours

Disclaimer#

The information in this article is provided for research and educational purposes only. Aura Information Security does not accept any liability in any form for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of or reliance on the information contained in this article.