Perfecting your Phish Simulations — The 85% Sweet Spot for Optimal Learning

I don’t normally choose Phishing as a research topic because I think the literature is saturated with insights. However, I see that many companies struggle with a few important details when it comes to Phishing simulations:

- What is the optimal Phishing simulation click rate and what it entails

- How to achieve the optimal Phishing simulation click rate

- How company culture impacts learning from Phishing simulations

Running phishing simulations is essential for educating employees and refining their ability to recognise and avoid phishing attempts. However, finding the sweet spot between challenge and achievability is crucial for ensuring effective learning and behaviour change. Here are a few key considerations based on research.

The Eighty Five Percent Rule for Optimal Learning#

The Eighty-Five Percent Rule¹ research by Robert C. Wilson et al. (2019) posits that optimal learning occurs when individuals are correct 85% of the time, implying that the task is neither too easy nor too difficult. This applies in humans, animals and Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning. When tasks are too easy, learning can stagnate, and when they are too difficult, individuals can become frustrated and disengaged. This isn’t a new idea, according to the Flow Theory proposed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi back in 1990².

Wilson mentioned the 85 percent rule would be particularly applicable in perceptual learning, in which we gradually learn tasks by interacting with the environment. Perceptual learning is learning better perception skills to increase our ability to make sense of what we see, hear, feel, taste or smell. In our case, this translates to learning how to better spot a Phishing attack.

Applying this rule to phishing simulations would suggest that designing simulations such that approximately 85% of users successfully identify and avoid the phishing attempt could lead to optimal learning conditions. This would leave around 15% of users falling for the phishing exercise, which would signal a balance of challenge and skill, as initially suggested.

Otherwise, if too few employees fall for a simulation, the exercise might be too easy and may not challenge employees to think critically. If too many fall for it, it could be discouraging and detrimental to learning.

Applying the 85% rule helps in ensuring that employees are sufficiently challenged to critically assess emails and other communication, which could potentially be phishing attempts, while still maintaining a level of confidence and motivation to learn and improve their cybersecurity behaviours.

Adjusting the difficulty of simulations and monitoring the success rates over time can help with maintaining this balance as users become more adept at recognising phishing attempts, thereby fostering continuous learning and adaptation to evolving cyber threats.

Isn’t a 15% phishing simulation click rate target too high?#

It depends what you measure against. If it would be a real phishing attack and you get 15% clickers, yes it is too high.

Which one is better — getting high click rates during phishing exercises, when it’s safe to fail, or during a real Phishing attack?

The REAL goal of a phishing simulation is not to get to a low click rate, it’s to PREPARE your employees in case a real phishing attack, and EDUCATE them to spot a real phish. Those are 2 very different goals and you need to be very careful what you wish for. Aiming for low click rates (e.g. 5%) could actually work against the real goal here, which increases the risk of people falling for a real phishing attack when it happens.

Achieving the 85% Rule for Optimal Learning with NIST’s Phish Scale#

What gets measured gets managed — the first obvious step is to continuously monitor the success and failure rates of your phishing simulations. If the success rate is consistently above 85%, increase the difficulty of the simulations. Conversely, if the success rate drops significantly below 85%, consider reducing the difficulty or providing additional training resources.

How to do this in practice? There’s no point reinventing the wheel when NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) has already developed a good enough method for this, called Phish Scale³. The Phish Scale is a valuable tool that can help organisations in adjusting the difficulty of phishing simulations and assessing their effectiveness. It’s designed to help with better understanding the results of your phishing exercises and make the necessary adjustments to your training programs.

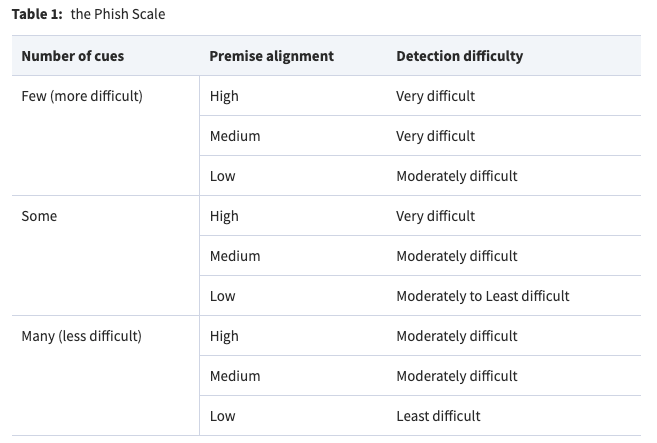

The Phish Scale works by evaluating two main components of a phishing email:

- Cues: These are the elements within the email that can help a user recognise it as a phishing attempt (e.g. grammar mistakes, suspicious sender or URLs, logo design, sense of urgency, etc). The Phish Scale rates the presence or absence of these cues to determine how easy or difficult it is to identify the email as malicious.

- Alignment: This refers to how well the premise of the phishing email aligns with the recipient’s role within the organisation. If the email’s context is highly relevant to the user, it’s more likely to be convincing.

NIST uses three categories to characterise the alignment: High, Medium, and Low.

1) High alignment

For high premise alignment, there should be a significant portion of the target audience for which the premise matches work responsibilities or practices, is highly plausible, and/or aligns strongly with an audience-relevant event. For example, if the recipient population is the finance department and the phishing message has a premise of a late or missed payment, the overall alignment is high.

2) Medium alignment

Medium alignment is achieved with either case: (i) when the premise has plausible but weak context alignment with a large portion of the target audience or (ii) when the premise has moderate context alignment with a small portion of the target audience. For example, if the recipient population mostly works in one physical location and the phishing message has a moderately pertinent premise for the few members of the recipient population who work in another physical location.

3) Low alignment

There is low alignment when the premise pertains to a topic that is not relevant or plausible to the target audience. For example, if the recipient population is the finance department and the phishing message premise pertains to a Call for Papers on biotech research or a similarly unrelated topic, the overall alignment is low.

The NIST Phish Scale also defines elements for the premise alignment, which the training implementer can use based on the target training population. Some of them are:

- Mimics a workplace process or practice: this element attempts to capture premise alignment with workplace process or practice for the target audience,

- Has workplace relevance: this element attempts to reflect pertinence of the premise for the target audience,

- Aligns with other situations or events, including external to the workplace: alignment with other situations or events, even those external to the workplace lends an air of familiarity to the message,

- Engenders concern over consequences for NOT clicking: potentially harmful ramifications for not clicking raise the likelihood to clicking,

The NIST research paper shows the stronger influence of premise alignment component over cues — i.e. the more relevant the phishing simulation context is to the user, the more difficult it will be to detect, as outlined in the table below.

In the context of maintaining the 85% rule for optimal learning, the Phish Scale can help organisations identify whether their phishing simulations are too easy or too hard, and make adjustments to ensure that employees are adequately challenged but not overwhelmed.

Putting it simply:

- If click rates are above 15% — make the phishing simulations easier by increasing number of cues or lowering the premise alignment (context) level

- If click rates are below 15% — make the phishing simulations more difficult by decreasing number of cues or increasing the premise alignment (context) level

If you have the means to tailor your phishing simulations to your target audience (and it’s great if you do), you can use the suggestions above to adjust the level of difficulty by designing phishing simulations that are contextually relevant to the employee’s role and responsibilities and department. The more relevant the email, the harder it might be for the employee to recognise it as a phishing attempt, thereby increasing the difficulty level. Also, some employees or departments (the IT/Security team) may be more familiar with cybersecurity principles and therefore may need more difficult phishing exercises.

However, if you don’t have the capabilities to tailor phishing simulations to different users/departments, but still want to hit the 85% learning sweet spot, you can adjust only the premise alignment variable. For example, align the simulations with something applicable to the whole organisation, such as:

- For medium/high premise alignment, choose alignment elements related to culture (e.g. health & safety, or productivity), field of work (software development, pharmaceuticals, finance/insurance, etc), or events that happened recently in the company

- For low premise alignment (easy to implement, but still relevant) — choose alignment elements related to tax refunds, courier deliveries, unpaid invoices, etc.

It goes without saying that if you are designing spear phishing campaigns, the way you match the phishing premise alignment to your target audience will be very important. As a rule of thumb, stick with high premise alignment elements for your exercise.

NIST researchers do mentioned that one of the main limitations with this tool is that all of the data used for the Phish Scale came from NIST. The next step in future research would be to expand the pool and acquire data from other organisations, including nongovernmental ones, and to make sure the Phish Scale performs as it should over time and in different operational settings.

The Caveats#

Equally important and quite coincidental, 3 days after the Eighty Five Percent Rule for Optimal Learning paper was published, a similar research by Eskreis-Winkler and Fishbach (2019)⁴ found that ’ failures can undermine learning, and that people learn less from failure than from success, on average. This effect was replicated across professional, linguistic, and social domains — even when learning from failure was less cognitively taxing than learning from success and even when learning was incentivized'.

According to their research, the main reason for users not learning from their failures is because failure is ego threatening, which causes people to tune out. They tend to look away from failure and not pay attention to it to protect their egos, and this becomes a barrier to learning.

This finding is directly opposing the 85% rule for learning research. There’s still hope though. Luckily, there are ways to address the learning barriers which come from failure, by promoting a culture of learning and a growth mindset which aids with the development of competence, skills and knowledge.

Regarding the ego threats to learning, 3 years later a follow-up research was published in 2022⁵ by the same authors (Eskreis-Winkler and Fishbach), which suggested ways to address the emotional ego barriers which prevent learning from failure. A lot of it also has to do with having a positive culture.

- Remove the ego from failure. Participants gained fewer insights from their own failures compared to their successes. However, they absorbed equal lessons from the failures and successes of others. This suggests that when their ego isn’t at stake, individuals are more receptive to learning from mistakes.

- Boost the ego to strengthen people’s self-confidence so they are resilient enough to confront failures and grow from them.

Remove the ego from failure#

The best way to detach one’s ego from failure is to learn from the mistakes of others. Since we aren’t personally involved in another person’s failure, it doesn’t threaten our ego. In fact, seeing someone else fail might even enhance our self-esteem. Observing another individual’s attempts and failures enables us to understand what not to do, without damaging our own self-worth or causing us to disengage.

For the purpose of our Phishing simulation discussion, this could mean a live workshop with a wide audience in the organisation, where an expert walks people through various phishing scenarios and click failures, thus removing the egos from the experience of falling for a phish.

Boost the ego#

There are multiple approaches to this, and all of them are related to how good (i.e. positive) the company culture is.

One method involves reshaping people’s perception of failure, transforming it into a foundation for confidence. For instance, individuals who have faced failure (i.e. fell for a Phishing attack) are encouraged to use their experiences to guide others. By offering advice, it implies that one has the capability to succeed rather than the absence of it.

The ego can also be strengthened by recognizing and reminding people of their skills, dedication, or proficiency. Experts often handle failure more gracefully because they are more confident in their dedication, shielding them from the detrimental effects of negative feedback.

Another strategy to bolster the ego is to perceive failure as a chance to learn. An experience that doesn’t go as planned becomes valuable when the objective is growth. In fact, those with a growth mindset, or the belief that their abilities can evolve, remain resilient amidst setbacks. People with this mindset don’t see failure as defining. Their self-assurance remains intact during such times, enabling them to focus on and learn from these situations.

Culture is more important than anything#

Lastly, as I mentioned in previous research articles, a critically important premise for optimal learning to happen in any organisation is having an underlying positive culture, for example no blame and shame. This way, when people click on a Phishing link, although they are accountable, they feel safe to report it and learning can germinate. Without a positive culture, the desired learning goals may be impeded by fear of repercussion or shame — situations when the brain is less likely to learn. In their 2022 research, Eskreis-Winkler and Fishbach also mention the importance of developing a culture which emphasizes learning from failure.

Future Work and Limitations#

As with any other research, there are other variables involved - especially when it involves people and complex processes such as learning, which can’t all be included in this single article.

An important aspect which can impact the effectiveness and applicability of the 85% rule for Optimal Learning in Phishing simulation programs is frequency. How often would Phishing simulations need to occur in an organisation so that optimal learning from them (according to the 85% rule) can happen? Quarterly seems too sparsely, and weekly is far too often. A best guess would be monthly, which is achievable with the right technology and approach. More research and data is needed for this, and I will leave this to future researchers and implementers in the field.

Research References#

- [1] Wilson, R.C., Shenhav, A., Straccia, M. et al. The Eighty Five Percent Rule for optimal learning. Nat Commun 10, 4646 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12552-4

- [2] Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience

- [3] Michelle Steves, Kristen Greene, Mary Theofanos, Categorizing human phishing difficulty: a Phish Scale, Journal of Cybersecurity, Volume 6, Issue 1, 2020,https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyaa009

- [4] Eskreis-Winkler, L., & Fishbach, A. (2019). Not Learning From Failure — the Greatest Failure of All. Psychological Science, 30(12), 1733–1744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619881133

- [5] Eskreis-Winkler, L., & Fishbach, A. (2022). You Think Failure Is Hard? So Is Learning From It. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(6), 1511–1524. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211059817

- Phishing cover image by Prawny from Pixabay

Disclaimer#

The information in this article is provided for research and educational purposes only. Aura Information Security does not accept any liability in any form for any direct or indirect damages resulting from the use of or reliance on the information contained in this article.